Benchmarking Non-shared Locks in Java

Last time we discussed scalability of j.u.c.l.ReentrantReadWriteLock and some alternatives. Some of the alternatives used a simple CAS (compare-and-swap) based spinlock as the internal writer lock. So, I was curious whether such custom spinlock makes sense against what we have in the standard library. This brief post is dedicated to benchmarking the ReentrantLock class against a number of other non-shared (exclusive) locks.

Before we go any further, I have to warn readers that the considered alternative lock implementations are not production-ready in any sense, so use them at your own risk. The below results were obtained on concrete HW and SW and may change a lot in a different scenario and not only. Needless to say that using a single lock on the hot path is usually a bad idea. I advise going with the standard library as the default choice. So, consider this post to be an unfair, non-scientific experiment done out of curiosity.

The full code of the benchmark and the custom locks is available in this repo.

Competitors

Our first competitor is the j.u.c.l.ReentrantLock class, in its both unfair and fair flavors. The common wisdom claims that fair mode comes at a high cost. But what does it mean in practice? In theory, fair locks prevent thread starvation, so if the cost is reasonable, say, 2-3x, it might be a good idea to use it in certain use cases. That's why we're considering fair ReentrantLock.

The first custom lock implementation we're going to use is a primitive CAS-based spinlock:

public class CasSpinLock implements Lock {

private final AtomicBoolean lock = new AtomicBoolean();

@Override

public void lock() {

while (!lock.compareAndSet(false, true)) {}

}

@Override

public void unlock() {

lock.set(false);

}

// ...

}

This spinlock is as primitive as it could be. Apart from this basic version, we're also including a simple backoff version of it. To lower the contention for the boolean flag, the backoff version does LockSupport.parkNanos(10) in the loop body. This flavor of the CAS lock is exactly what we were using in the previous blog post.

The next spinlock is a test and test-and-set one. The main difference is in the lock() method:

@Override

public void lock() {

long delay = MIN_DELAY;

for (;;) {

// busy spin until the lock is available

while (lock.get()) {}

// try to acquire the lock

if (!lock.getAndSet(true)) {

return;

}

// back off

LockSupport.parkNanos(delay);

if (delay < MAX_DELAY) {

delay *= 2;

}

}

}

This spinlock should do a better job than the CAS one in terms of cache coherence traffic - most of the time it reads the lock flag from the local core's cache line and only does an atomic test-and-set operation when it saw that the lock was just released. The lock also uses an exponential backoff technique to reduce the contention. The exponential backoff should do a better job than the constant backoff used in the previous lock. So, in theory, this lock has the chance to demonstrate better throughput than the CAS spinlock.

The next spinlock is the well-known ticket lock. Again, in the theory, it has a number of advantages over previously listed spinlocks. The ticket lock is built on top of two atomic counters. The first one stands for ticket numbers: any thread attempting to acquire the lock increments the counter to get its ticket number. The second counter means currently served ticket: the thread with this value is considered to be the lock owner. When the lock owner releases the lock, it increments the currently served counter. Due to this design, the ticket lock it provides fairness guarantees, i.e. it guarantees FIFO ordering of lock acquisition. Another advantage is that there is only a single counter increment and a busy-wait read on the second counter on the hot path. We're not going to focus on the source code, but you may find it here. Worth mentioning that ticket locks may be found in Linux kernel.

Last, but not least on our list is the MCS spinlock. The algorithm is named after the authors. Just like the ticket spinlock, the MCS lock is a fair lock. The main idea behind it is to organize the waiter queue in a singly linked list where each waiting thread spins on its own node. When the current owner releases the lock, it updates a flag on the node belonging to the waiter in the head of the queue. Hence, MCS spinlock is very efficient in terms of cache coherence traffic: the number of messages exchanged by the cores on each lock acquisition is O(1), unlike O(N) in the ticket lock. We're going to test two flavors of MCS lock. The first one is not a spinlock since it uses LockSupport.park()/unpark() facility to suspend and resume threads in the queue. This flavor should perform close to the fair ReentrantLock. That's because the standard class uses CLH algorithm to implement fair lock mode. The CLH lock uses an implicit linked list, but otherwise, it's close enough to the MCS lock. The second MCS lock flavor is a proper spinlock. Again, you may find a variation of the MCS spinlock in Linux kernel.

Since our test stand is not a NUMA machine, we're not considering NUMA-aware locks, such as hierarchical locks or lock cohorting.

Benchmark

The benchmark we're going to use focuses on the average execution time per lock -> some work in the critical section -> unlock chain of calls. Thus, we're interested in the throughput rather than latency distribution or power efficiency of the locks under test. Since we want to understand lock scalability properties, the work done in the critical section is kept short enough.

Here is the benchmark itself:

@Benchmark

public void testLock(BenchmarkState state, Blackhole bh) {

final ThreadLocalRandom rnd = ThreadLocalRandom.current();

state.lock.lock();

// emulate some work

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_WORK_SPINS; i++) {

// access a counter (shared memory)

state.sum += rnd.nextInt();

}

bh.consume(state.sum);

state.lock.unlock();

}

We're going to run this benchmark varying the number of threads from a single thread (no contention) to the number of available CPU cores (highest contention).

Results

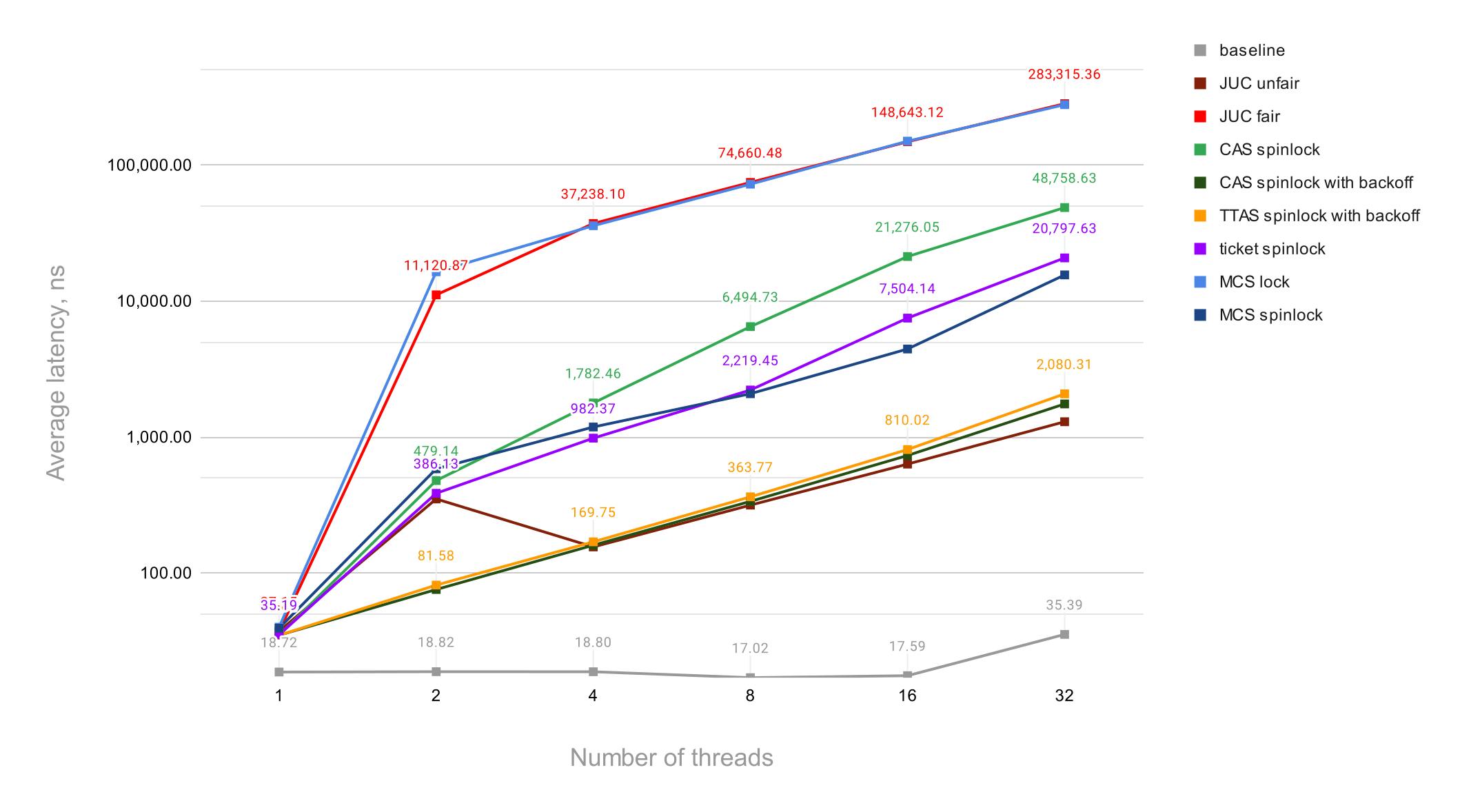

The below results were obtained on a GCP's e2-highcpu-32 VM with 32 vCPUs (Intel Haswell), 32 GB memory running Ubuntu 20.04, and OpenJDK 17.0.1. The following chart represents all results. A text version of the results is also available here.

Notice that the vertical axis has a log scale and stands for the average operation latency in nanoseconds.

The first thing to notice is that the baseline (think, work done in the critical section) result at the very bottom of the char is constant for any number of threads except for 32 threads where it gets 2x slower. Most likely that's because of the hyper-threading cores available on the VM. Hyper-threading sibling cores share arithmetic logic units (ALU) and since we're doing some number crunching in the critical section, that becomes the bottleneck when all cores are in use.

Next, the fair mode of ReentrantLock comes at a very high cost. In the 32 threads scenario, the difference in latency is 218x, hence two orders of magnitude. Anyone who uses fair ReentrantLock should be aware of potential performance implications. As we expected, the non-spinlock flavor of the MCS lock comes close to the fair ReentrantLock.

There is a number of outsiders among our hand-crafted spinlocks. The first one is the CAS spinlock without a backoff. It heavily suffers from contention over CAS operations over a single atomic flag (think, a cache line). Surprisingly, ticket and MCS spinlocks, which were very promising in theory, follow the basic CAS spinlock closely in terms of the average latency. Although the difference between the CAS spinlock and the MCS spinlock is 3x, the MCS spinlock is still far away from the group of winners.

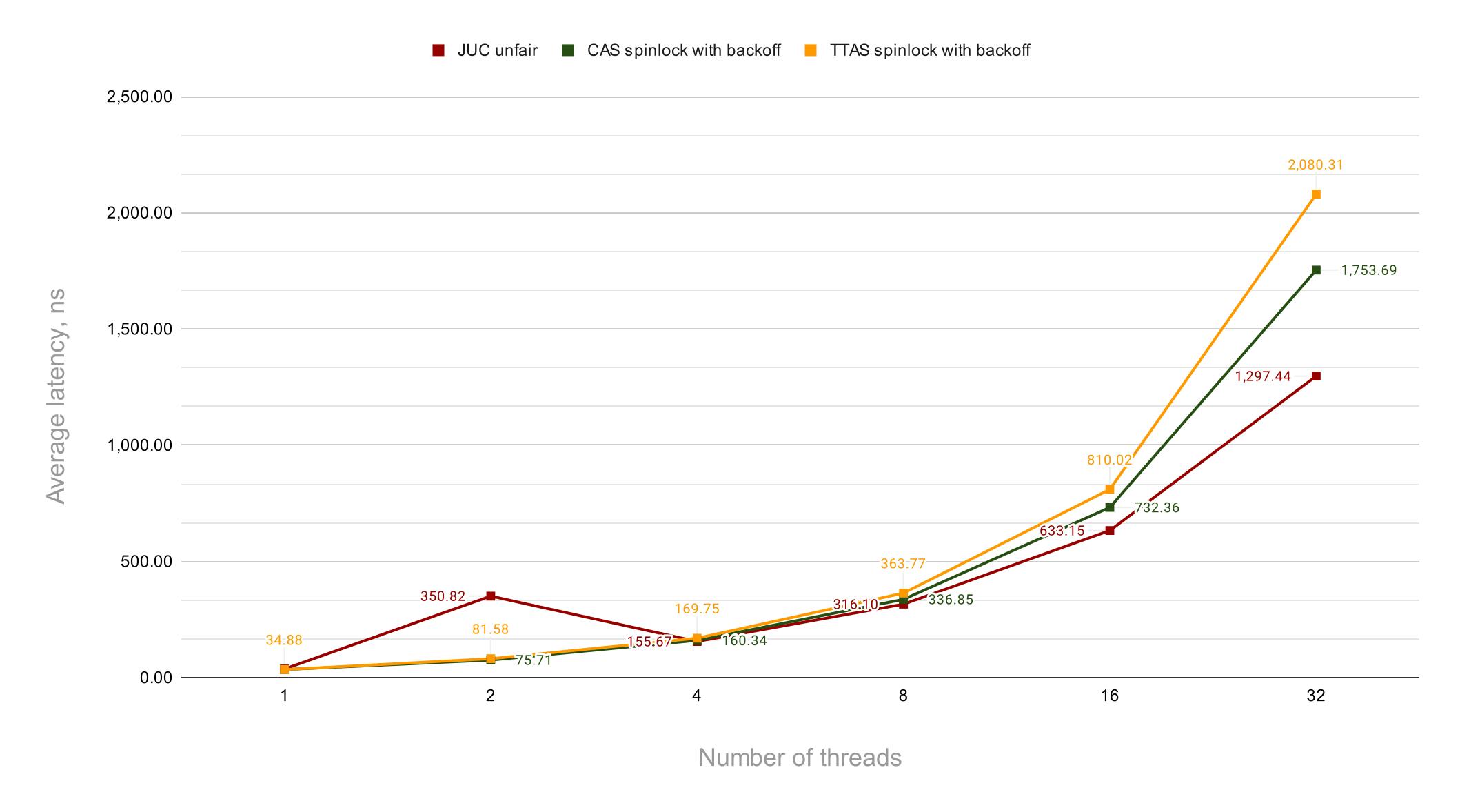

Let's remove the outsiders from the chart and get rid of the log scale. This should help us when analyzing the winning group.

The first thing to note here is that a CAS spinlock with a primitive, constant time backoff implementation performs better than the TTAS spinlock. The latter has a slightly more complex code for the spinlock itself and definitely a more complex exponential backoff mechanism. Surprisingly, the CAS spinlock provides lower average latency on all thread counts, so it makes no sense to deal with the TTAS spinlock, at least in the considered benchmark scenario.

The second observation is that unfair ReentrantLock does a really great job overall. Our custom spinlocks show a better result with 5x lower average latency only when the benchmark is run on 2 threads while the standard lock wins on 8 threads and beyond. In the highest contention scenario, ReentrantLock's latency is 26% lower than the CAS spinlock's one.

Lessons learned

Hopefully, this toy benchmark can serve as another argument to use the unfair ReentrantLock as the default choice in any Java application. The standard lock provides solid performance and can be beaten by a custom lock only in a concrete scenario. On the other hand, the fair ReentrantLock mode has to be used cautiously when you're certain that the fairness guarantee outweighs the performance impact.

As for the custom spinlock classes, it's not a one size fits all story. Depending on the concrete hardware and usage scenario a simpler lock may outperform more complex locks while in theory, it should be the other way around.